What I Will Say in D.C.

November 11, 2024 is the 31st anniversary of the Vietnam Women's Memorial

On Veterans Day this year, I will have the privilege of speaking at the Vietnam Women’s Memorial.

My connection to the site began in 2014 when I traveled to our nation’s capital to visit the Vietnam Veterans Memorial—a trip I felt I had to make as part of my writing about the Vietnam Era.

After an emotional time at the reflective wall, I walked somberly across the lawn in search of a quiet place to collect my thoughts. I found myself at the Vietnam Women’s Memorial.

I sat on a bench and caught my breath. I wrote up notes from the wall and also captured observations in the moment (click here to read them). Little did I know then that the peace I found there would help sustain me through the many long years of studying and writing about Vietnam.

I began this writing journey when a friend said to me, after a devastating job loss, “I think you should write about Vietnam.”

I began then, naturally, to write about my father’s evacuation of 1000 South Vietnamese in April of 1975. Knowing I would need support and guidance I enrolled in a master’s program in creative writing.

During my studies and after reviewing yet another draft that was deeply informed by the many letters my mother wrote to her parents during our 10 months there, one of my mentors said, “Your mother is turning out to be a real hero in this story, too.”

“Your mother is turning out to be a real hero in this story, too.”

Until then, I had done what so many of us do. Are trained to do. Expect so much from women and recognize so little of what they do.

My mother had managed a family of nine, plus various pets, across three foreign countries over five years. She’d supported my father, kept us all healthy, packed and unpacked, overseen various servants and helpers (as was the custom at that time), and still managed to write detailed missives home describing the, at times, harrowing conditions without losing heart.

Hero, indeed.

In 2014, as I sat near the Women’s Memorial composing my thoughts, none of this was on my mind. I saw the memorial as what it had been first conceived to be: a tribute to the nurses who served so valiantly in the war zone of Vietnam.

In a 2023 interview at the Women’s Memorial, founder Diane Carlson Evans said:

How has the mission [of the memorial] evolved? . . . we named the project the Vietnam Nurses Memorial project because I thought that's all the women who were in Vietnam then after we began it we started getting letters. . . and it was like this epiphany that I had:

’Oh this is not just about nurses.’

Women were serving all over the world in a variety of capacities and in Vietnam even, so we expanded it and changed our name to the Vietnam Women's Memorial project . . . there were the photo journalists and the traffic controllers and women in in administration who also served really so we didn’t want this monument to be literal, we wanted it to be about women so any woman could connect to this monument and feel the recognition and the honor she deserves.

I would like take this opportunity to expand the honor to those women who went to Vietnam as wives and unofficial supporters, those previously unsung heroes like my mother.

A recent book, Absolution by Alice McDermott, focuses on some of these women. However, she portrays the women as primarily victimized by their experiences. A New York Times book review uses the term “blunderer wives” and describes that tragic state of affairs this way:

McDermott asserts her revisionist focus in the novel’s third sentence: “You have no idea what it was like. For us. The women, I mean. The wives.”

The review finishes with:

. . . as American wives overseas in 1963, they had . . . a near-total lack of agency or power; a choice between parroting their husbands’ opinions or operating independently in the margins, to limited and uncertain effect.

Please, let me beg to differ. As early as 1950 those women, the ones who were “just wives” were organizing themselves into the AWAS, the American Women’s Association of Saigon.

My mother proudly sent several copies of their newsletter to the states.

AWAS published many things including guides to Vietnam, cookbooks, datebooks, and regular newsletters. They created events, built community, and connected with the local population in myriad ways.

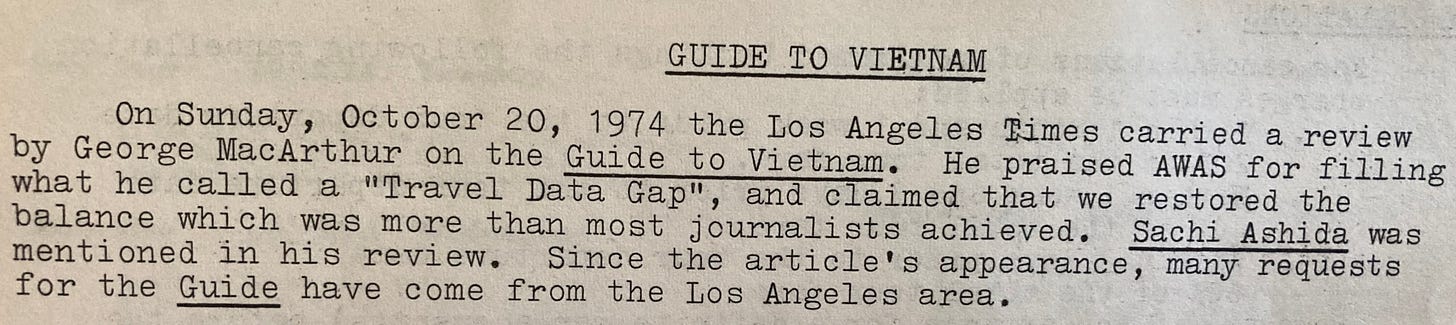

While you may be tempted to think these were simply local endeavors, their works were noticed by both the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times,

Note that the LA Times writer claimed that the AWAS restored the balance of information “which was more than most journalists achieved.” These were not blundering women!

In all the AWAS writings I can find, I find no apologetic woe-is-me tone, no sense of powerlessness, and absolutely no hand-wringing or catastrophic suffering despite the obvious difficulties they endured taking care of their families while living in a war zone.

When my mother wrote home in September 1974, she mentioned the power of the women’s efforts:

We had our first PTA meeting last week – - and a real crowd turned out – – The community is growing rapidly. This week I have conferences with the teachers. So, this one-time man’s world is slowly turning into a “normal” world, which has been long overdue.

When I have the honor of speaking at the Women’s Vietnam Memorial next month, I will humbly ask that women like my mother, those who were wives but so much more than “just wives,” be taken into the fold as the other non-military veterans of the Vietnam War have been.

To repeat the words of the memorial founder, Diane Carlson Evans:

. . . [it’s] about women so any woman could connect to this monument and feel the recognition and the honor she deserves.

A note to my mom (1936-2004)

Dearest Mom,

This is a much-belated salute to you.

I hope you feel it: all the honor you deserve.

Your loving daughter,

Kat

Pictured here: My mom at Vung Tau Beach, 1974. She always was one for driftwood and caring for “big sticks.”

A little bit about me:

In addition to curating “Stories of Vietnam” I am the author of For the Love of Vietnam: a war, a family, a CIA official, and the best evacuation story never heard.

how my father ended up in Vietnam running a propaganda radio station beginning in 1972,

our family life blended with historical context from July 1974-April 1975, and

the incredible evacuation of 1000 South Vietnamese that my father orchestrated in late April 1975.

With much gratitude, November 11 you will be in my prayers. ✌️🤎

I absolutely love your take on this.