"Mail Call: Letters from/to Vietnam"

Year-long exhibit in Albany, N.Y. captures the words of war

The tears come. Always.

They are not so much sentimental, I think, as they are the result of coming in contact with the the vast panorama of pain and emotion that the Vietnam Era wrought.

And I forgot to bring any Kleenex.

Yesterday, I was honored to be a guest at the New York State Office of General Services (OGS) Opening Reception for the yearlong exhibition: Mail Call: Letters From/To Vietnam.

Earlier this year I submitted several letters for consideration and one was chosen to be included in the physical exhibit at the NYS Vietnam Memorial Gallery at Albany’s Empire State Plaza. All three are included in the online, which you can view here.

Yesterday morning, as the first speaker—OGS Commissioner Jeannette Moy—began reciting lines from letters written by soldiers in country, the tears rose up in the corners of my eyes.

Soon I felt in good company as I saw the male speakers sitting in front of me also brushing their cheeks.

Indeed, when U.S. Army Colonel James Tom took to the stage he lauded our beautiful weather—and the allergies that come with it. Soon, however, it was clear that what reddened his eyes was, not pollen, but the deep longing to set a terrible wrong right at long last.

After the ceremony Colonel Tom we was kind enough to share his notes with me. I share some of them with you now, hoping you can hear his humor, his sincerity, his absolute desire that we all reach out to any Vietnam Veteran we encounter and say, “Welcome home.”

This was just part of Colonel Tom’s address:

It is common practice today, to treat our warriors and our veterans very well. We treat them with respect and admiration. We welcome them home and thank them for their service and bravery.

But that wasn’t always the case.

Fifty years ago, our nation did not treat returning warriors from the war in Vietnam very well. The majority received no recognition, no fanfare, no parades, and no welcome home ceremonies.

In fact, many returned to criticism, and in some cases outright scorn. Their families endured the hardship of separation and, in many cases, the loss of a loved one without support of their communities and nation.

Our Vietnam veterans could have turned their back on society. Instead, they changed the culture in how we treat our returning warriors today.

[He turned his gaze directly to the Vietnam Veterans in the audience.]

It was you who ensured that we would never forget our warriors and our veterans ever again. And so the reason I’m here today, is to right that wrong by honoring you Vietnam Veterans with us today.

I’m also here to remind and encourage all Americans to find ways to continue to honor you —this generation of heroes and their families—who maybe haven’t received this thanks and honor.

Colonel Tom in turn introduced Joe Madeira, the Director of Curatorial and Visitor Services, who explained the criteria for the letters in the Mail Call exhibition:

We ranked our ideas in the form of questions and here were the top three

What reminded soldiers of home?

How did families react?

What are we fighting for?

The end result of letters displayed in a stark-white design—emblematic of a memorial—is so powerful, yet simple.

The exhibition offers a deeply human perspective on a conflict often defined by politics and statistics. These letters, often written in the quiet moments in between, reveal the raw and unfiltered emotions of young men and women facing unimaginable circumstances.

Through their words, and their family’s words, we gain insight into the complexity of war, the diversity of individual experiences, and the universal longing for connection and meaning.

The emotional range found in these letters is vast. Some letters express fear, questions, and anger, while others convey moments of hope, camaraderie, and even humor. A soldier might describe missing homemade cookies in one paragraph and then tell of a horrific night operation in the next. These emotional contradictions reflect the psychological toll of war and the resilience of those who endured it.

Moreover, the letters show the diversity of the soldiers themselves-men from different racial, geographic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Their voices provide a mosaic of American life during the 1960s and 70s, highlighting shared struggles and individual perspectives. The variety of voices in the exhibition breaks down the monolithic image of the Vietnam soldier and replaces it with a more nuanced, humanized narrative.

Ultimately, these letters tell a broader story of the Vietnam War not through strategies or outcomes, but through the lived experiences of those who fought it. They reveal how war touches individuals and families, how it changes them, and how they try to hold on to love and humanity amid chaos. Through ink on paper, these soldiers left behind more than memories-they left a testament to the cost of war and the enduring power of personal connection.

That the letter my teenage brothers wrote to my father on April 6, 1975 when he was still in Vietnam in a valiant effort to both stay on the job (CIA) and plan the rescue of nearly 1000 South Vietnamese, is testament to the diversity embraced by this exhibit. They were not soldiers, but they embody in their young language and earnest words, the yearning for their father and their earnest trust that he will return.

These are their letters:

Dear Dad,

We had a real hard trip and had to stay in Guam and Honolulu because the number one engine broke down.

Sorry I didn't get a postcard in Hawaii, but I sent all my love in this letter. Now we're in Boise. It's snowing. It just started tonight. Today was 33. Ice cold. When we got here, we didn't have any clothes, so we froze.

It's so nice to be back in the U.S., but it would be nicer if you were here too. I hope the days go by fast. You know what? Today we went to McDonald's. It was pretty good. We also went downtown and looked for clothes. Most of us got coats, but I didn't get one.

It seems like it changed here, but I can't wait to see Virginia. Oh yeah, Grandpa said it's too cold to fish. I love you and hope to see you soon. Goodbye with love.

Love, your son, Mike.

And then the letter from Chris.

Hi, Dad. How have you been? Fine, I hope, because I want to see you soon.

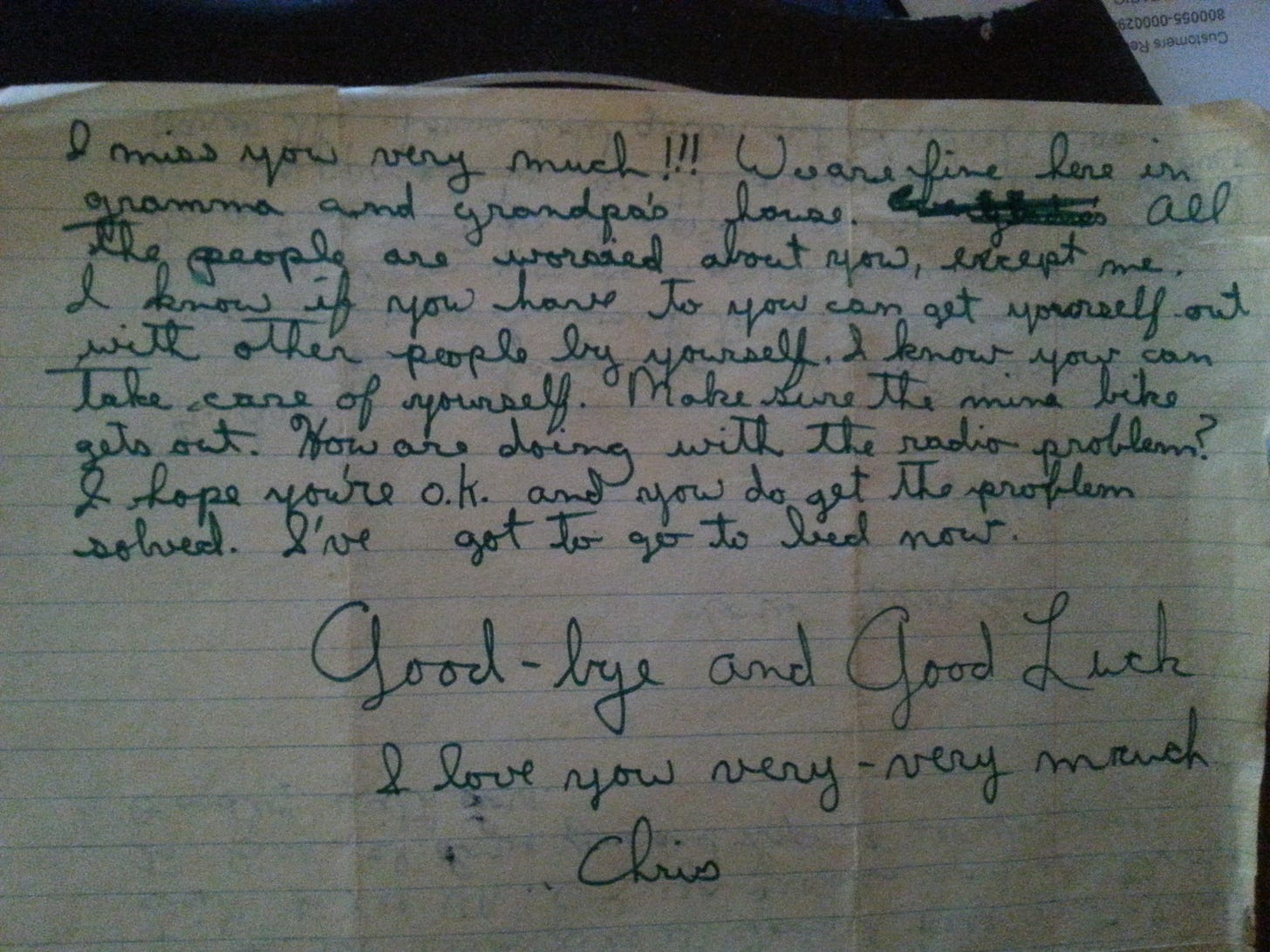

I have been wondering when you are going to get home. Is it supposed to be sometime in early June? That's supposed to be the original time, right? Have the household items gotten out of Vietnam? I miss you very much. We are fine here in Grandma and Grandpa's house. All the people are worried about you except me.

I know if you have to, you can get yourself out with the other people by yourself. I know you can take care of yourself. Make sure the mini bike gets out. How are you doing with the radio problem? I hope you're okay and you do get the problem solved. I've got to go to bed now.

Goodbye and good luck. I love you very, very much.

Chris

P.S. About that mini-bike . . . sadly, it never got out

If you enjoyed this, please like, share, comment, and/or subscribe.

Many thanks always,

Kat

A little bit about me, Kat Fitzpatrick:

In addition to curating “Stories of Vietnam” I am the author of For the Love of Vietnam: a war, a family, a CIA official, and the best evacuation story never heard.

how my father ended up in Vietnam running a propaganda radio station beginning in 1972,

our family life blended with historical context from July 1974-April 1975, and

the incredible evacuation of 1000 South Vietnamese that my father orchestrated in late April 1975.

View draft history

I would love to get up to Albany to see this exhibit. Letters are so powerful.

The New York City Vietnam Veterans Memorial on Water St in lower Manhattan has excerpts from letters carved on it, including one from my late friend Cathleen Cordova, who served as a civilian with Army Special Services Service Clubs. Letters to and from New Jersey soldiers are prominently displayed at the museum attached to the New Jersey Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Holmdel, NJ.

Letters can bare the soul by what they don’t say as much as what they do. They are a window into lives, experiences, and the times during which they were written. It’s no wonder historians consider them to be such valuable primary sources.

I wonder if their electronic equivalents will have the same lasting effects as the handwritten ones.