Lying to make life "easier"

The Paris Peace Accords of January 27, 1973 were not about peace

“I’m lying to make my life easier,” a fifth grader said to me yesterday. He wanted me to think him sincere but his clenched fists and cheeks the color of raw meat told another story. Those clues and the fact that I was chaperoning him during an in-school suspension told a vast truth underlying his statement.

I wonder sometimes if the same rationalization ever went through National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger’s head as he bushwacked the cratered path to the 1973 Paris Peace Accords.

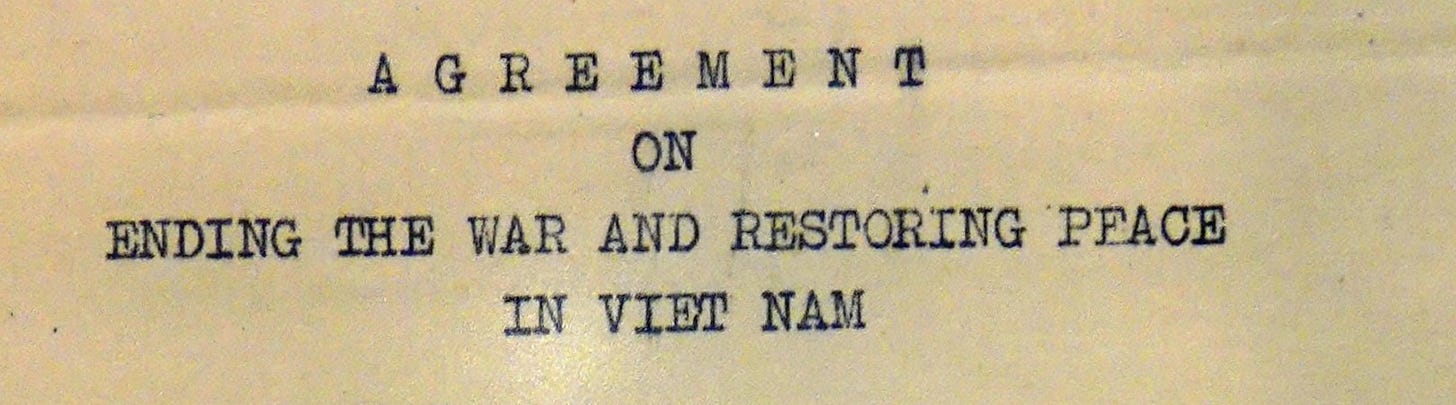

Officially titled the “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Viet Nam” the many-times-revised document was not so much an agreement as a lie.

But it was making some lives easier. At least for a time.

For Kissinger and President Richard Nixon, it provided the illusion of control and the appearance of an honorary exit.

For American families—especially those whose loved ones were POWs—it provided the relief that their fathers, sons, brothers, lovers would soon be home to stay.

(As I write about this benefit, I am flooded with emotion for, of course, this was no small thing and, possibly, the one good and great result of this negotiation.)

For my family and the other Americans who remained involved in the everyday life of the Vietnamese, it was a clinging burr.

The summer before the Paris summit, my father, a CIA officer in the psychological warfare department, was reassigned from “his long-standing Korean broadcast” to Saigon where he would head up a radio program aimed at mellowing out the North Vietnamese Army’s aggression. (Somewhat akin to World War II’s Tokyo Rose program.)

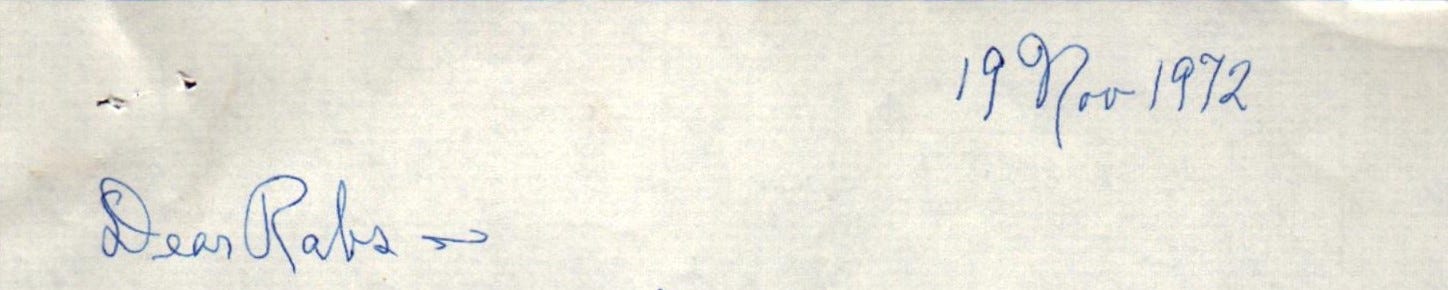

In November of 1972, even as Kissinger was doing his black magic behind the scenes, he wrote to my mother’s parents:

The commies are really something. By every measure of military and political warfare, they have lost, but they keep on talking as if they had won. Well, Peking and Moscow appear to realize they have had it and I hope Henry the K pushes them to the wall in Paris.

He finished the letter with a heartfelt wish:

I hope we will not have to pull stakes right soon since Nancy and the kids are happy and not even really settled [in Taiwan] yet.

At the time of his reassignment, we were not allowed to reside in Vietnam and my mother was very happy to land near Taipei where we already had many American friends.

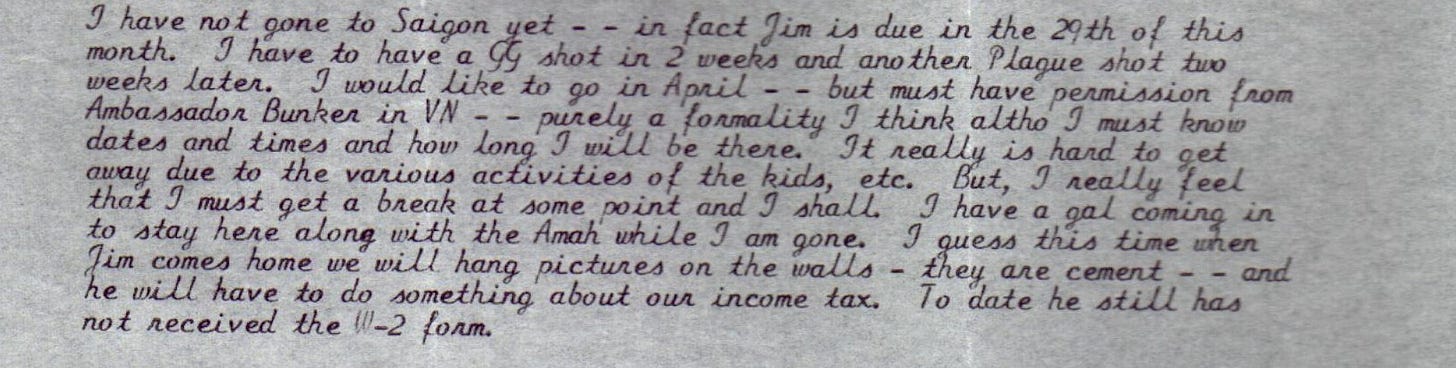

In March 1973, just two months after the accords, she wrote home with no mention of anything politic, except that she hoped to visit my father soon but had to apply to the embassy to enter.

I would like to go [to Saigon] to visit in April, but I must have permission from Ambassador Bunker in VN. Purely a formality, I think . . .

In Karen Kaiser’s soon-to-be-published memoir, Gardens in the Midst of War, she recounts a dinner party conversation in July 1973 in which the electricity goes out—yet again—and the candle-lit conversation turns to talk of the ongoing fighting.

One guest says:

“I heard the explosions, too,” said Lawes. “Seemed close . . . Wasn’t the Paris Peace Agreement supposed to end all this?”

Indeed.

When my family arrived a year later in July of 1974, wide-eyed and eager to be reunited with my father, the same question would linger over our ten months there:

Where was the provision for peace that guaranteed us safety

and was meant to make our lives “easier?”

What’s your understanding of the January 27, 1973 Paris Peace Accords? I hope you’ll leave a comment and let me know.

Find out more about my work and books at Kat-Fitzpatrick.com. My narrative nonfiction story, For the Love of Vietnam: a war, a family, a CIA official, and the best evacuation story never heard is available by request wherever books are sold.

“When the crowded Vietnamese refugee boats met with storms or pirates, if everyone panicked, all would be lost. But if even one person on the boat remained calm and centered, it was enough. It showed the way for everyone to survive.”

—Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese Buddhist Monk (1926-2022)

Thank you for the Thich Nhat Hanh quote. Even in exile from his country for all those years he remained calm and true to himself. I agree that the root of the lie (and violence for that matter) is fear and panic. It seems that there was no one in the "boat" of the conflict who was not without panic. And fear. Not unlike the boy you describe, Kissinger and Nixon, and all involved were lying to ease their own fear.