Greetings,

Welcome to the chapter December 1974, excerpted from my 2023 publication, For the Love of Vietnam: a war, a family, a CIA official, and the best evacuation story never heard.

It’s a blend of the personal experiences of my family and the historical circumstances of the time.

Click here if you would like to see a full synopsis and how I tell the distinctly different stories of :

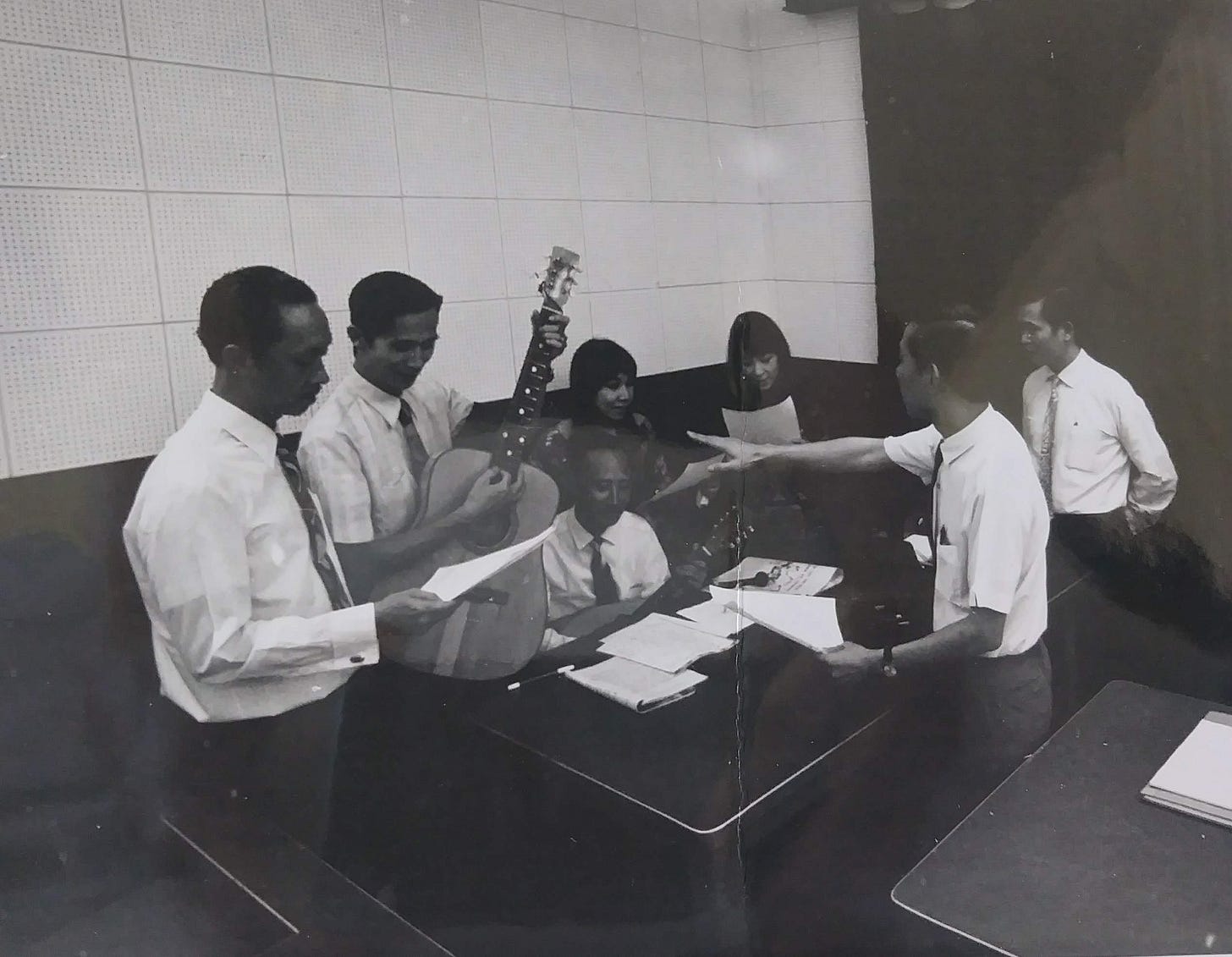

how my father ended up in Vietnam running a propaganda radio station beginning in 1972,

our family life blended with historical context from July 1974-April 1975, and

the incredible evacuation of 1000 South Vietnamese that my father orchestrated in late April 1975.

I hope you enjoy this glimpse of history—if you do, please leave a comment so I know!

Chapter: December 1974

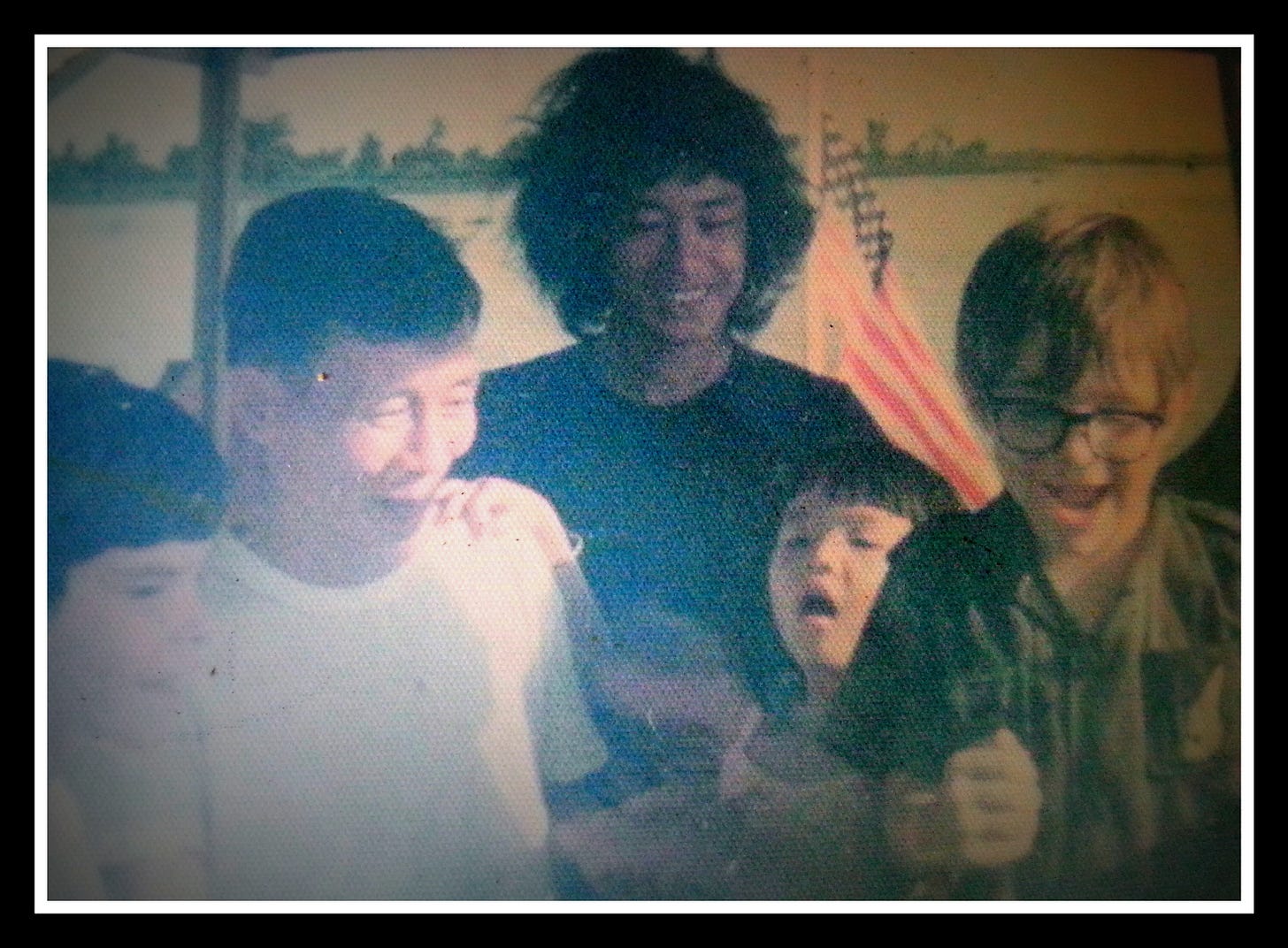

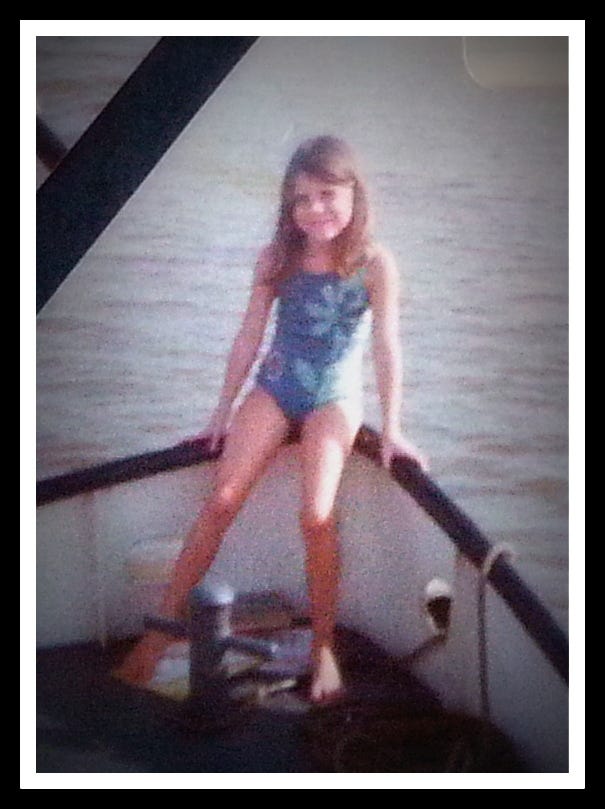

Despite all evidence to the contrary, my parents doggedly kept things as normal as possible. In early December, they were planning a family trip to Thailand for Christmas, still hoping for a washer and dryer, and making time for unique Saigon experiences. One Friday, my father took the afternoon off of work, despite his pressing workload, and all nine of us boarded a small charter boat to take us on a cruise along the Saigon River for several hours.

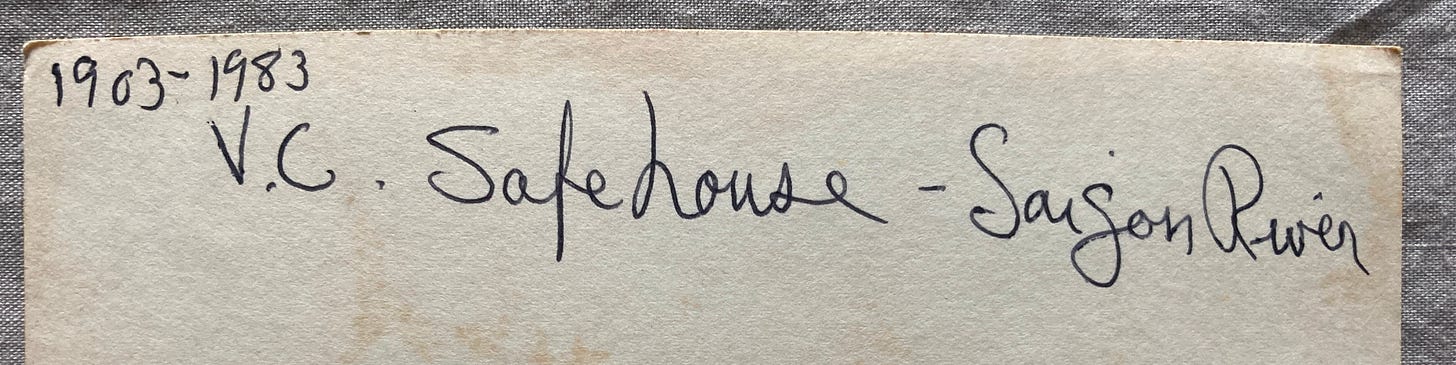

Though it was a “wonderful, relaxing day” complete with a picnic lunch, reading, and an opportunity to take steering lessons from our young South Vietnamese tour guides, we could not keep thoughts of war completely at bay. The sun was beginning to sink toward the horizon when Chris pointed toward the green-swathed shore dotted with low-lying buildings.

“There could be Viet Cong anywhere over there,” he said to me.

I pursed my lips. I could imagine that there might be danger where he pointed but my eight-year-old brain could not fathom exactly what that might mean. What did a Viet Cong look like? Would I know one when I saw it? What would it do to me? I stared hard at the trees and bushes, wishing I could diminish the invisible threat by making it miraculously appear.

Unfortunately, my wish was about to come true—or quite nearly true. We didn’t get to see any identifiable Viet Cong but began to feel their presence at uncomfortably close range. For one, we were informed that a South Vietnamese employee at House Seven—a typesetter—had been arrested due to suspicious activity. When interrogated, he confessed to being a Viet Cong infiltrator, a spy for the National Liberation Front.

My father’s company car was immediately switched out and we had the plates changed on the family station wagon, but that hardly made us safe again.

House Seven was a close-knit group of people who spoke freely among themselves and came and went as they pleased. The two-story building was actually an old warehouse, its shabbiness meant to disguise its top-secret PSYOP mission. It was not even heavily guarded, another attempt to keep it under the radar. As an insider, the VC spy had access to much information about every American working at the station, including our house address.

“Obviously we can’t move,” my mother wrote in a half-hearted attempt to soothe her parents. “The VC probably knew where we lived before we moved in, anyway.”

It soon became apparent that they did indeed know of our location. One day upon arriving home from school, I heard an unusual noise coming from the second floor near my bedroom. I took the stairs two at a time, my little legs trembling with the effort. As I topped the last step, I realized that the noise was coming from my brother’s room, which, though it was located right next to mine, had an outside entrance that could only be reached from the main house via a short balcony walk that overlooked our “little pool” in the central rock garden below and opened to the rooftop garden above.

As I stepped out onto the short balcony the sound sheered out of the open door of his room. It was loud and grinding and not at all reassuring. I peered around the doorway to see my father, on his knees, pressing a smoking drill into the cement wall of my brother’s bedroom. The perspiration dripping from his forehead startled me more than the noise. I don’t think I had ever seen him sweat.

The white wall was strafed with gray gouges. They were wide but not very deep. Mr. Bi was looking on with studied intensity but even I could see the doubt in his face. John was watching with curiosity but not much conviction himself.

My father saw me and let the drill fall silent.

“Wh – what are you doing?” I asked.

“Trying to make a tunnel,” Dad answered. “Your brother heard sounds on the balcony.”

“Sounds?” I said.

“Your mother is afraid it might be the VC,” he replied almost laconically. After all, what is one to do when living in such circumstances? He examined the torn-up bit, avoiding my eye. “She wants a way for John to be able to get to your room at night without going outside.”

My heart lurched in my chest and a cold sweat pricked the nape of my neck.

Viet Cong in the center of our house? The enemy Viet Cong? Right next to where I slept? I was sorry I had ever wished to see them.

It is worth repeating here that the Viet Cong were communists but they were distinct from the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) which was an organized military similar to any other country’s. The VC was the primary guerrilla force that occupied pockets of South Vietnam and was responsible for so much of the hardship that American soldiers endured—they operated in a coordinated but hardly traceable system, faded in and out of sight like ghosts, and blended in with the South Vietnamese villagers.

The NVA, by contrast, moved in battalions, directed by a Hanoi-based leadership. In December, they began in earnest to take over parcels of land in remote areas. These were not strategic or valuable sites, but they were tests. Would the U.S. retaliate? Would there be any pushback for their escalated breach of the Paris Peace Accords signed in January 1973? Communist Party First Secretary Le Duan was watching the American political scene carefully. It was not long before he made up his mind that the extended and messy congressional debate in Washington D.C. was dissolving any backbone America had had in regard to Vietnam. It was becoming clearer and clearer that they would not be pumping any more funds into supporting the South Vietnamese Army. Le Duan concluded that the odds were truly in favor of the North’s plans for further military advances.

In the last week of December, the NVA made a move on Phuoc Long, a provincial capital 75 miles northeast of Saigon. This was a step up from the previous “land grabs.” From a military standpoint, it was not a great loss as the city was located too far from Saigon to be a strategic gain, but it was a devastating blow to the South Vietnamese government.

The AVRN held out for a week under heavy attack but by January 7, 1975, they lost control of the city. The fact that the United States did not respond at all was demoralizing to the South and was the crack of a starting gun for the North. Le Duan made a speech to his colleagues the day after the province was captured encouraging them to “create conditions for a general uprising in 1976 to liberate all of South Vietnam” or—if opportunities presented themselves earlier—perhaps even in 1975.

The loss of Phuoc Long, which inspired three days of mourning in Saigon, marked the true beginning of the end, though no one realized it at the time.

Excerpt taken from the 2023 publication of For the Love of Vietnam: a war, a family, a CIA official, and the best evacuation story never heard.

If you already have a copy, consider buying one for a local library or high school teacher! The more people who are thinking about the 50-year anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, the better.

Does anyone else see the irony in the current US Consulate HCMC (Saigon) sitting on a street named after the man who was First Party Secretary when the US military ran tail-between-their-legs from Vietnam?